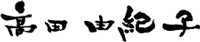

Yukiko Takada ARTIST STATEMENTS

The roots of my artwork are in classic calligraphy.

Calligraphy is how what was originally the purely practical act of writing characters with a brush as a means of communication transformed as the culture evolved into the act of writing the characters in an aesthetic manner, and the glorification of that kind of writing became known as sho or shodo in Japan.

It originated in China and developed as a cultural expression in countries that used Chinese characters, spreading from China to Korea, Vietnam and Japan.

In Japan we write not just the Chinese characters that we call kanji, but also the phonetic script called kana (or hiragana) that is native to Japan. We write with India ink called sumi and brush on handmade mulberry paper called washi.

So I said that the roots of my work are in classic calligraphy.

When you set out to do sho, which is more modern calligraphy, first you learn classic shodo. I started learning the classic works of Gan Shinkei (Yan Zhenqing) and Oh Gishi (Wang Xizhi).

You learn how to write the character itself through copying works of the past masters, and from how the character is put together, you learn technique and how to give the character expression. It is not possible to learn the form of the character first, and then start expressing yourself once you are able to write the character itself.

I started out showing mostly kanji based works.

A kanji character can have many strokes, and there are many lettering styles such as square style, running script and grass script, so there are many choices for expression. I was fascinated by the many ways to be expressive and I would make pieces with just one or two kanji characters written boldly on a huge piece of paper, or I would make beautiful Chinese style poems called kanshi, composed of 28 characters each.

Kana (hiragana) characters on the other hand seemed more feminine and weak to me, so I didn’t enjoy writing them very much, and I was not very good at making kana works.

** Kana are a cultural form unique to Japan, supposed to have originated with the native Japanese script used in the women’s literature of the time like The Tale of Genji.

Also, a kanji is an ideograph that expresses a meaning in the character itself, while kana are a phonetic syllabary and have no meaning on their own if not strung together to form words, which for me personally felt weak, and I did not feel they were good for me as a means of expression.

But then, though I considered myself to be making art by applying my own brush to write a kanji character that already had a meaning, as I continued to create kanji works, I started to feel that I was really just tracing out a meaning that was already there in the kanji, and that there was no self-expression happening. The more ideographic the nature of the characters I worked on, as opposed to phonetic characters, the more I felt the power of the kanji was too strong, and that the character I was writing were just tracing in ink on a piece of paper, and I began to feel like there was nothing of my own expression in it.

That is when I decided to try expressing myself using characters with simple forms that did not have any meaning of their own.

The shape of the character could have been anything, but I chose the kana character for the syllable “no” because it could have a lot of variation in the way it was written. In the beginning I was just practicing writing “no” with my brush on paper, but after going through 100 or 200 sheets of paper, and writing “no” 1,000 or 2,000 times, it never came out completely the same, and each one started to look like a different character to me. Perhaps if I were deliberately trying to write in a mechanical manner I could do it the same every time, but I was surprised by how I would almost never make the same character when I was just simply putting brush to paper and continuing to write. Each brush stroke was a combination of the speed at which I was working, my mood at the time that I was writing, the condition of the sumi ink that I had ground up, the hardness of the brush, the thickness of the paper - each became an individual element that I could see in the brush stroke.

Perhaps the characters would look exactly alike to a third party looking at them. Depending on the person I suppose they might look different.

What one thinks is strongly individual, in others’ eyes is basically the same “no”.

That is how I began to feel. That on a daily basis is what I feel as I go through life now. The way you live and feel and the strong sense of individuality that grows out of that, actually in other people’s eyes is just the life of a third party. But that is definitely where each single human being finds his existence.

The “no” kana character only has a sound, and even when it’s put together with other characters has no meaning of its own - it has no power as a character at all, but I felt that I could express something through it with my brush stroke. By bringing a personality to this stand-alone character, and by gathering those individuals together, I believed that I could make them have meaning and expression.

It seems to be just like when listening to music from foreign countries, you can tell if it is a light-hearted piece of music or something dark, even if you don’t understand the words. I think that even if the meaning of a character isn’t understood, you can be told of what I want to write through following the brush stroke from its beginning to its end. I believe that is by far a more powerful thing than writing a single kanji or ideographic character (like when you write the “ai” kanji which is going to be understood as love).

When people write words to communicate something, they are not aware of what they are doing from when they start writing until they finish, and only when they have finished writing does that group of characters begin to have meaning and purpose. And the word or sentence that comes from what they have finished writing is what they use to communicate with others.

I invite you to consider my “no” works as something similar to that.

Just like conventional sho calligraphy, I am writing out words that I want to communicate with a variety of emotion happening from when I start writing the characters until I finish. Because what I write is just the syllable “no”, it’s hard to know whether it’s done well or badly, or to tell what its meaning is. People whose mother tongue is Japanese or people who are learning Japanese will read it as the sound “no”. Foreigners may hear the phonetic sound “no” and take it to have the negative meaning of the English word “no”. But I invite you to take it as the stand-alone character and as the character itself that is created by the brush stroke.

I would be pleased if you can get a feel for the whole body of characters from the overall brush strokes as you look at the brush strokes that form this group of characters.